What The Microorganisms In Our Gut Can Do To The Biochemistry In The Body

They do so many things that it's difficult to keep track of all that they do.

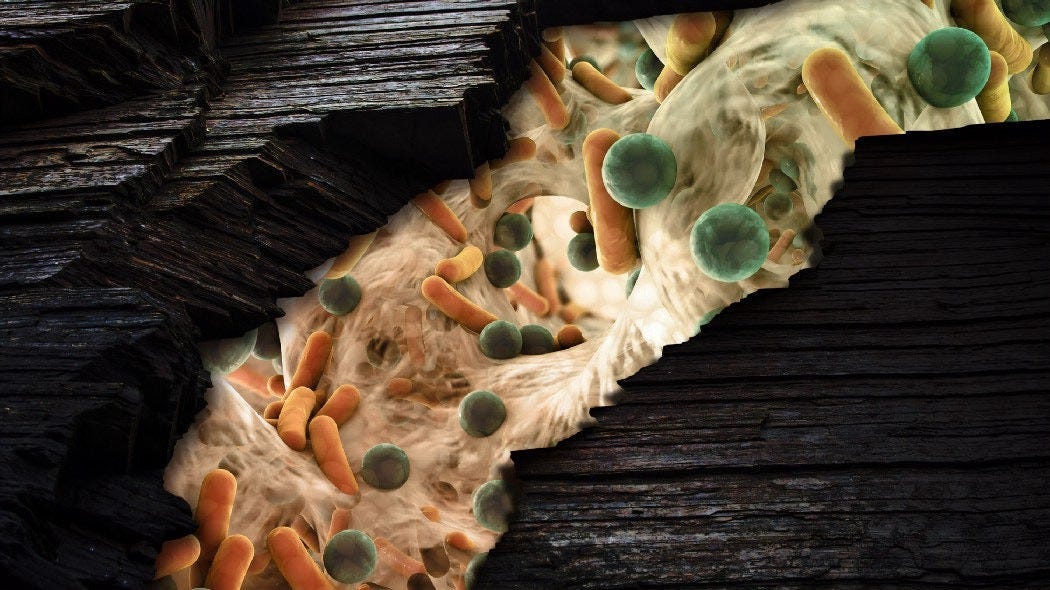

Our intestines are long and can contain approximately 100 trillion live bacterial microorganisms at any one time. These microbes comprise a diverse array of strains and species. Collectively, we know it as our gut microbiota, microbiome or microflora.

We have both our small and large intestines. As their environments are markedly different, different strains and species will tend to dominate the populations in those different regions.

For example, Lactobacillus species are predominantly found in the small intestine, while Bifidobacterium species tend to prefer being in the large intestine. Also, different strains and species will possess different adherence capabilities to the mucus linings of our intestines.

The population counts of the bacteria in our guts can influence many different functions in the body, which we may know or not know about. It just so happens that all these bugs are biochemical factories — they take in a certain chemical and biochemically process it (or metabolise it) into some completely new, different chemical, which has the ability to signal or influence how another cell can behave.

Hence, getting a balance of this biochemical factory activity is necessary for balancing out the different chemicals being metabolised and produced, which will then balance out how our body behaves in a biochemical manner.

That affects our digestive health.

These microbes help to break down food particles in our gut. Our digestive system produces lactase enzymes to break down lactose, for one.

When these cells aren’t producing enough lactase enzymes, the bacteria in our gut take over and break down the lactose into methane gas, hydrogen gas and other short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which then results in the development of symptoms associated with lactose intolerance, such as bloating, cramps, flatulence and loose stools.

Lactose Intolerance And What It Indicates About Our Digestive Systems

We tend to think of our digestive system at a very simple level. We eat food, our stomach acids break it down, our intestines absorb it, and whatever that isn’t absorbed is excreted into the toilet bowl.

So when our gut isn’t producing sufficient digestive enzymes to break down the major components of our food, such as proteins, carbohydrates and fats, we’d see that the body attempts to compensate by using some other process to break down those foods — and that will result in symptoms of indigestion appearing, or we’d see the development of a perceived food intolerance.

They affect our immune system functions.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Biochemistry Of Human Health to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.